Coaches like to preach worrying about the things a team can control and setting aside all the rest, which is a good message — right up until the moment the skies open and lightning strikes in the middle of a football game.

Or before the game begins if you’re the New Mexico Lobos. While traveling to play Auburn for a date on Saturday, New Mexico’s plan was diverted from Montgomery to Mobile. From Mobile, the Lobos used buses borrowed from the University of South Alabama. The Jaguars even sent food.

“[New Mexico] just said they needed some help, and so [South Alabama deputy athletics director Daniel McCarthy] was able to rally the troops quickly,” South Alabama athletics director Joel Erdmann told AL.com. “And it’s pretty admirable that people responded in the manner that they did. [Football chief of staff] John Clark … got them some pizzas for the road. They landed at [Mobile’s] Brookley [Field], got on four South Alabama buses and had pizzas waiting for them.”

On Saturday, the start of the Miami Hurricanes game against the visiting Ball State Cardinals was delayed more than two hours due to weather. North of Florida’s Coral Gables, in Gainesville, the Texas A&M Aggies led the Florida Gators 10-0 when the contest was paused at the end of the first quarter due to lightning.

Every program has a plan. During the offseason, operations managers crisscross the country for site visits then meticulously piece together flow charts for any conceivable contingency, including bad weather. But when the rain or lightning or remnants of a hurricane blow through, all those best-laid plans are still at the mercy of Mother Nature and, more practically, the often miserable conditions of the visitors locker room.

“You’re stuck in this crappy locker room,” said Pitt coach Pat Narduzzi, “and you don’t want to be in a crappy locker room more than you have to be.”

So, what do teams do when they’re squeezed into tight quarters for an indeterminate delay, sweaty and exhausted and hungry? Players try to sleep. Coaches attempt to refine the game plan. Operations staffers might even head to the concourse in search of a few dozen pizzas. In other words, it’s an all-hands-on-deck effort to keep 80-some players happy and comfortable in an utterly unpleasant situation. NCAA guidelines stipulate a 30-minute delay if there is a lightning delay within an eight-mile radius of a stadium; if there is another lightning strike during that time period, the clock restarts.

In 2024, we’ve seen other extended delays in Minnesota, West Virginia and Virginia during the early weeks of the season, and more interruptions are all but guaranteed.

“It does take its toll because players and coaches are used to a rhythm and a routine of a game day,” said Paul Federici, football operations director at the University of Iowa, “and this is one that is part of that disruption of rhythm that can’t be controlled. You talk through and plan for contingencies, most of which you may never use, but it’s good planning.”

There’s no perfect blueprint for handling the inevitable, but teams that have endured it at least leave with a good story to tell.

Chris LaSala remembers standing in the press box at Stillwater’s Boone Pickens Stadium in February 2016, looking out at the sprawling expanse of land that seemed to stretch endlessly outward toward an unreachable horizon.

LaSala, University of Pittsburgh’s associate athletics director for football administration, looked at his counterpart from Oklahoma State in amazement.

“It’s really flat out there,” he said.

“Oh, yeah,” the Cowboys operations manager responded. “When it storms, you can see it coming from miles away.”

Seven months later, with Pitt and Oklahoma State tied at 38 entering the fourth quarter of their Week 3 showdown, LaSala stared out toward that same horizon.

It was a wall of black, interrupted regularly by immense flashes of lightning — “dark and scary,” LaSala said.

Scary enough for the game to be delayed, with officials sending both teams off the field — the Cowboys to the cozy confines of the home team’s locker room, and the Panthers to a broom closet.

“I just remember crawling over people,” Pitt coach Narduzzi said. “Guys laying on the ground. There’s nowhere to walk. You’re crawling between people’s legs just to get to the next player.”

Pitt’s coaches were trying to go over plays and keep the players focused for the resumption of play, but that’s an impossible task in such cramped conditions.

“Most athletes during those times get completely cold and lose adrenaline,” said former Pitt wideout Tre Tipton, who was a freshman on that 2016 team. “And when your adrenaline goes down, you really understand what your teammates and you smell like.”

LaSala said his job was largely about keeping players comfortable — finding snacks and peanut butter and jelly sandwiches leftover from halftime or simply clearing enough space so it’s possible to stretch out and rest.

In this case, however, LaSala said matters were made worse because of how late in the game the delay occurred. Staff members already had started packing up the locker room for a quick postgame exit, and now equipment managers were busy unpacking the truck again to get players fresh undershirts and socks.

For Oklahoma State, the experience was a bit better.

Before the delay, Pitt had been red hot, erasing a 31-17 deficit with two long touchdown runs and a scoop-and-score on defense. But when the game resumed after a nearly two-hour delay, the Cowboys had a little extra spring in their step as compared with the downtrodden Panthers, who had four straight drives end in a punt before a late interception.

Rennie Childs scored on a 1-yard touchdown run to put the Cowboys up 45-38 with 1:28 to play, and after securing the victory, coach Mike Gundy credited the delay with sparking Oklahoma State.

“I’ll be real honest with you: The delay saved us,” Gundy said in his postgame news conference. “We got a lot of coaching out of it. When the delay happened, I was OK with it, because I felt like we needed it to make some corrections. I felt like this was a good thing for us.”

That’s a summation Narduzzi agrees with, though he remembers it a little differently.

“It’s against the rules, but from everything I heard, Oklahoma State was sitting in their team room watching the first, second and third quarter of the game,” Narduzzi said. “I don’t want to throw Gundy under the bus. But Gundy knows.” — David Hale

The scene inside Iowa City’s Kinnick Stadium after midnight on Sept. 18, 2022, was strange in several ways.

First, a football game was still being played between Iowa and Nevada, after three lightning delays that totaled 3 hours, 56 minutes. The game began on Sept. 17 and concluded at 1:39 the following morning with the Hawkeyes prevailing 27-0. Iowa had been prepared for delays, but as the night went on, some stadium security staffers went home and some new fans showed up.

Paul Federici, University of Iowa’s longtime director of football operations, saw students walking in with 12-packs of Twisted Tea. Another student brought his dog into the stadium and sat behind the Iowa bench. A fan found a massive bag of popcorn that concession workers normally divide into smaller portions.

“This young fella had the full-size clear plastic bag of popcorn on the seat next to him behind the bench,” Federici recalled. “It had to be like a cubic yard of popcorn, but he was just crushing it in the last part of the game.”

The food rations for the teams were a bit less accessible, especially as the evening dragged on. Both Iowa and Nevada had “burned through” their in-game and postgame food, Federici said, due to the repeated delays, so they partnered up and used the vendor Aramark to restock both locker rooms. Iowa also contacted a Hy-Vee grocery store for ready-made sandwiches and wraps.

Any delay interrupts routines for teams, but multiple delays can add stress, especially for players debating whether to remove their pads and for those going through multiple warmup sessions, only to be called back.

“We came back out at one point and maybe ran a play or two, and we’re sent right back in again,” Federici said. “That on again, off again is not desirable, for sure, but we’re dealing with weather, so it’s not a great certainty.”

Iowa worked with the National Weather Service and game operations staff to keep both coaching staffs informed as the night went along.

“It’s tough being on the road, and selfishly, I get a good feeling making sure that teams we host have the information and service and attention they need to get in and out, keep all their kids safe and have a good, competitive game,” Federici said. “Everybody, step by step, was kept really well-informed.

“That was a long evening.” — Adam Rittenberg

The state highway patrol in Iowa is called upon to clear congested routes for VIPs, including college teams traveling to and from games. On this afternoon, troopers were given a different assignment: getting the University of Iowa’s student managers from Iowa State’s Jack Trice Stadium in Ames to a local Hy-Vee grocery store and other eateries and back again as quickly and as safely as possible.

The Hawkeyes needed food after players ate their post-game meal during the first of two lightning delays at rival Iowa State. When the second delay arrived, during the second quarter, Iowa launched its food plan. Every week, Iowa’s Federici begins tracking weather six days before kickoff then takes a closer look 48 hours beforehand. The Hawkeyes knew bad weather was possible and had contingency plans, but they didn’t reach out to Hy-Vee and other places until the delay hit.

“We knew which stores were closest to campus,” Federici said. “We did not preorder anything. That’s a balance between making a purchase and committing to something that you don’t need and then having a lot of waste versus having a solid contingency plan.”

Federici contacted a “short list” of options, targeting places that had ready-made cold sandwiches or wraps.

“We made the calls and quickly figured out who could help us and who couldn’t,” Federici said. “Then we put people in the car and sent them along their way, with the university credit card.”

They returned with about 60 sandwiches or wraps, which helped Iowa players refuel during the long delay. There were other adjustments, including a shortened halftime. Federici had no complaints about the visitors locker room at Jack Trice Stadium, which was climate-controlled and allowed Hawkeyes players to remain “relaxed, hydrated and fueled.”

The game took 5 hours, 53 minutes to complete, but Iowa came away with an 18-17 triumph, making the wait worthwhile.

“It’s minute by minute,” Federici said. “We’re all improvising as we go.” — Rittenberg

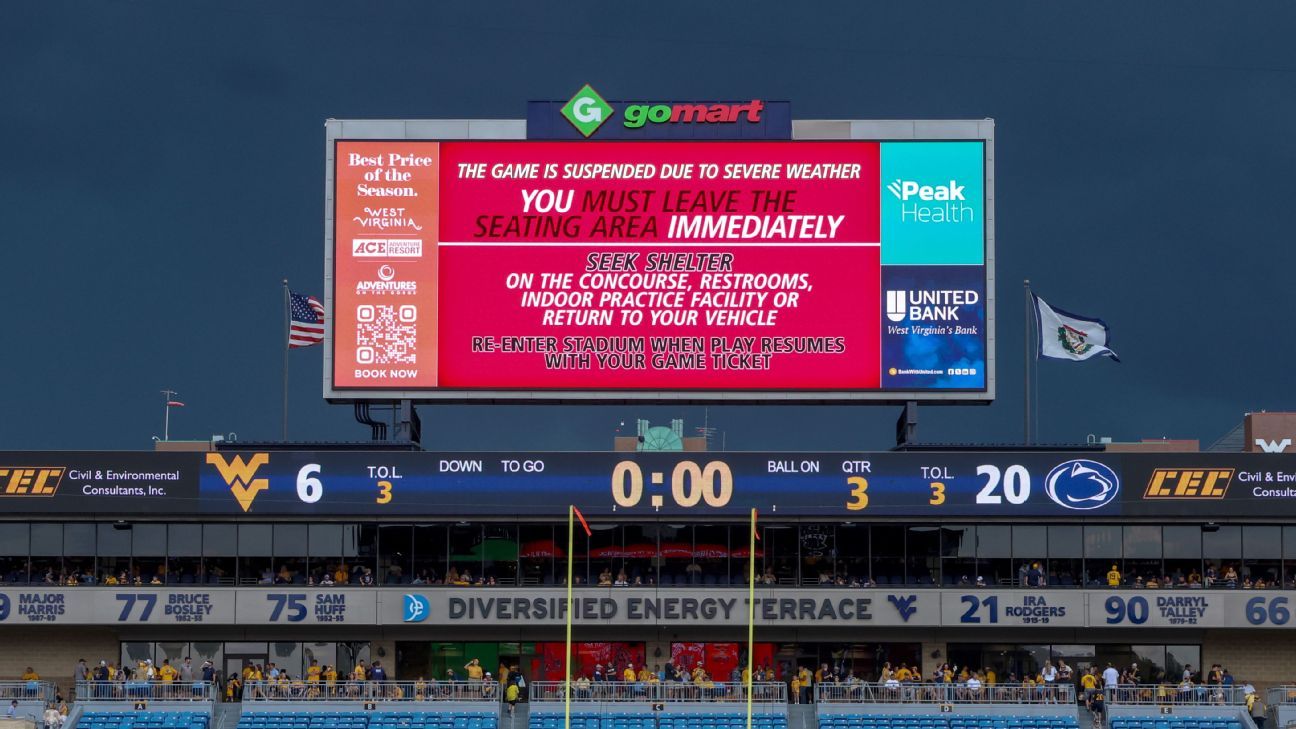

As the season opener neared, Penn State football chief of staff Kevin Threlkel and Patrick Johnston, West Virginia’s assistant athletic director for football operations, tracked an ominous weather pattern.

There were projections ranging from a quarter of an inch of rain to two inches. They concluded that an afternoon storm was likely in Morgantown, and they began preparations for a moderate delay.

“What made this one different is we didn’t know how long it was going to be,” Johnston said. “If it’s going to be an hour, two hours or longer, have them take off pads, get off their feet and stay semi-locked in.”

Penn State, the visiting team, faced more obstacles. Threlkel made sure to stock up on socks, pants and other dry clothes if the players got drenched. The team placed a sandwich order at a local restaurant, which would deliver boxes during the first half. The visitors locker room at Milan Puskar Stadium is tight, and the Nittany Lions put benches and chairs in a covered tunnel just outside so that players could stretch and review film on tablets — which is permitted during games for the first time this season.

“We had a good game plan,” Threlkel said.

The storm came just after halftime, an ideal spot for a delay. Penn State didn’t even need its dry clothes.

When the delay began, West Virginia spread out, putting its offensive players in the weight room and the defense in the locker room. Haley Bishop, WVU’s director of sports nutrition, sprang into action, making sure players loaded up on protein and carbs, especially those prone to cramping. Bishop worked with a caterer to order sandwiches and had smoothies, beef jerky, fruit and even some junk food available for the pickier in-game eaters.

“Once [the delay] was announced, I told them it would be a while, ‘Here are three options, pick two,'” Bishop said. “I have a couple guys who really like Sour Patch Kids and Pop-Tarts. That’s not something I would normally give them, but I was definitely passing those out. They’re quick carbs and make it a little more fun.”

Players and others huddled around Johnston’s laptop, tracking the radar. At one point, staff from both teams and game operations officials met and outlined the logistics around a restart, but a nearby lightning strike pushed things back 30 minutes.

“That’s what makes it miserable, thinking that you’re going but then you’re not,” Johnston said. “I had a pretty good feeling it would be out between 3:50 and 4 [p.m.], based on what we were seeing on the radar, unless we caught one random [strike].”

After 2 hours, 19 minutes, the second half finally kicked off. Penn State maintained a comfortable lead and won 34-12, as the game ended at 5:59 p.m.

“We were really happy with how the players handled the situation, how we responded after it,” Threlkel said. “In those situations, we try to stay positive, instead of getting down.” — Rittenberg

When severe weather stopped the game in the second quarter, Cavaliers director of football operations Lindsey Morris knew exactly what to do.

The previous year, against James Madison, Virginia had learned a hard lesson during a weather delay that lasted more than an hour. The Cavaliers had Uncrustables sandwiches and pretzels to feed their players during the break but eventually ran out of snacks. When it returned to play, Virginia blew a fourth-quarter lead and lost. Coach Tony Elliott was adamant that the next time Virginia faced a weather delay, he wanted to be prepared with much more food.

So, as Virginia headed to the locker room against Richmond, Morris and the team nutritionists figured they would hop in their cars and go pick something up. But they soon discovered all roads coming back to Charlottesville’s Scott Stadium were closed.

Didn’t know we were playing the @CanesFootball today too…#UVAStrong | #GoHoos

️ pic.twitter.com/eOBa6qb7lp

— Virginia Football (@UVAFootball) August 31, 2024

Morris quickly called Virginia deputy athletics director and chief financial officer Steve Pritzker, who phoned Aramark, the company that provides food for the stadium’s concessions stands. Morris said she would take anything they had. Within 30 minutes, Aramark delivered to the Cavaliers’ locker room pulled chicken, baked beans, French fries, hot dogs, buns and sauces — food that had already been made but would have been thrown out with the concession stands closed during the delay.

If that was not enough thinking on the fly to solve a problem, Morris quickly had another one to solve. The hallway where the Cavs generally set up the tables for their snacks and postgame meal was being used by the coaching staff to go over plays from the first half and discuss the game plan. The locker room itself was so crowded with players, cheerleaders, support staff and others taking shelter from the storms that there was only one available space to set up the meal.

The bathroom.

“Before you get into our locker room, you walk through the bathroom — not the stalls, per se, but right around the corner there are stalls,” Morris said. “So, you walk through and that’s where we set the food up, which was absolutely disgusting. But when you’re hungry, you’ll do it.”

Morris said one player made his plate of food and sat on a toilet to eat it.

“It was just a really crazy experience, and I wish that I would’ve gotten it on video because people won’t believe you when you say that you set up a meal outside of urinals to make sure that they’re getting fed for a rain delay,” Morris said with a laugh.

Aramark brought so much food, players were able to have seconds. Morris said the company is still calculating how much the Cavaliers owe. But the plan to feed the team during the 2 hour, 17-minute delay worked. Virginia won 34-13.

“Everybody was trying to make sure these guys were fed,” Elliot said in his postgame comments. “They stayed very upbeat, stayed very engaged. Many times, you don’t get a shot at redemption. Really proud of the staff and guys for finding a way to finish.” — Andrea Adelson

The post Planning, patience and PB&Js: Tales of surviving weather delays appeared first on Patabook Sports.