As Heather Guo strolls down the streets of Manhattan in her burgundy qipao, passersby turn their heads to catch a glimpse, as if she was a character from a Wong Kar-wai film. Meticulously hand-stitched with threads of gold and silver, her long silk qipao, a traditional Chinese dress dating back to the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912), is adorned with delicate floral patterns that seem to whisper stories from a bygone era. Wearing the dress today, she weaves together the contemporary charm of New York City with the timeless allure of 1950s Shanghai.

Guo, who was born in Shanghai and moved to the U.S. when she was 15 years old, is an avid qipao collector. She boasts over 300 qipaos from around the world, dating back to the 1950s and ’60s, and recently opened her shop, Xiangjiang Vintage—which specializes in carrying the traditional dress—in New York City’s West Village, attracting Asian American customers with her vast catalog of styles.

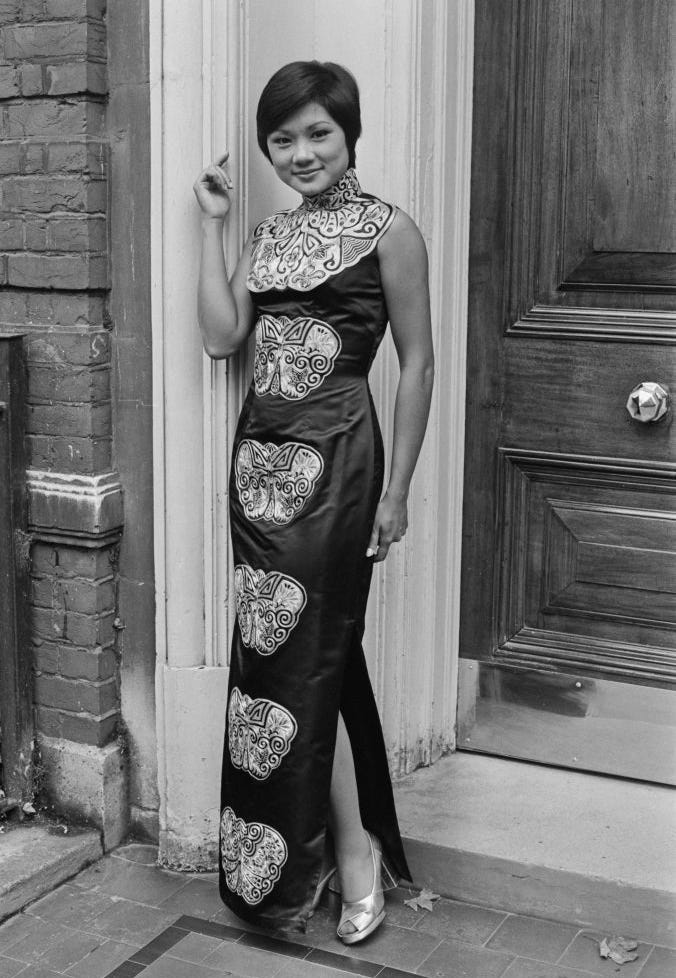

The qipao, also known as the cheongsam in Cantonese, is often made with embroidered silk, and features high collars and straight lines. The dress has had many iterations over the centuries, and heavily influenced the world’s perception of Asian women.

In the 1920s, as women broke free from Confucian social norms, the tailors producing the dresses embraced the Western flapper styles, which were characterized by short hemlines and a fitted bodice. Antonia Finnane, a history professor at the University of Melbourne and author of How to Make a Mao Suit: Clothing the People of Communist China, 1949–1976, told ELLE.com that “the qipao evolved from a square-cut, looser-fitting style—initially related to Manchu dress—to the sheath style in the 1930s. This transformation reflected the changing perception of women’s bodies as they gained more freedom and were no longer confined to traditional roles. They no longer had to hide themselves in the voluminous garments that their mothers and grandmothers wore.”

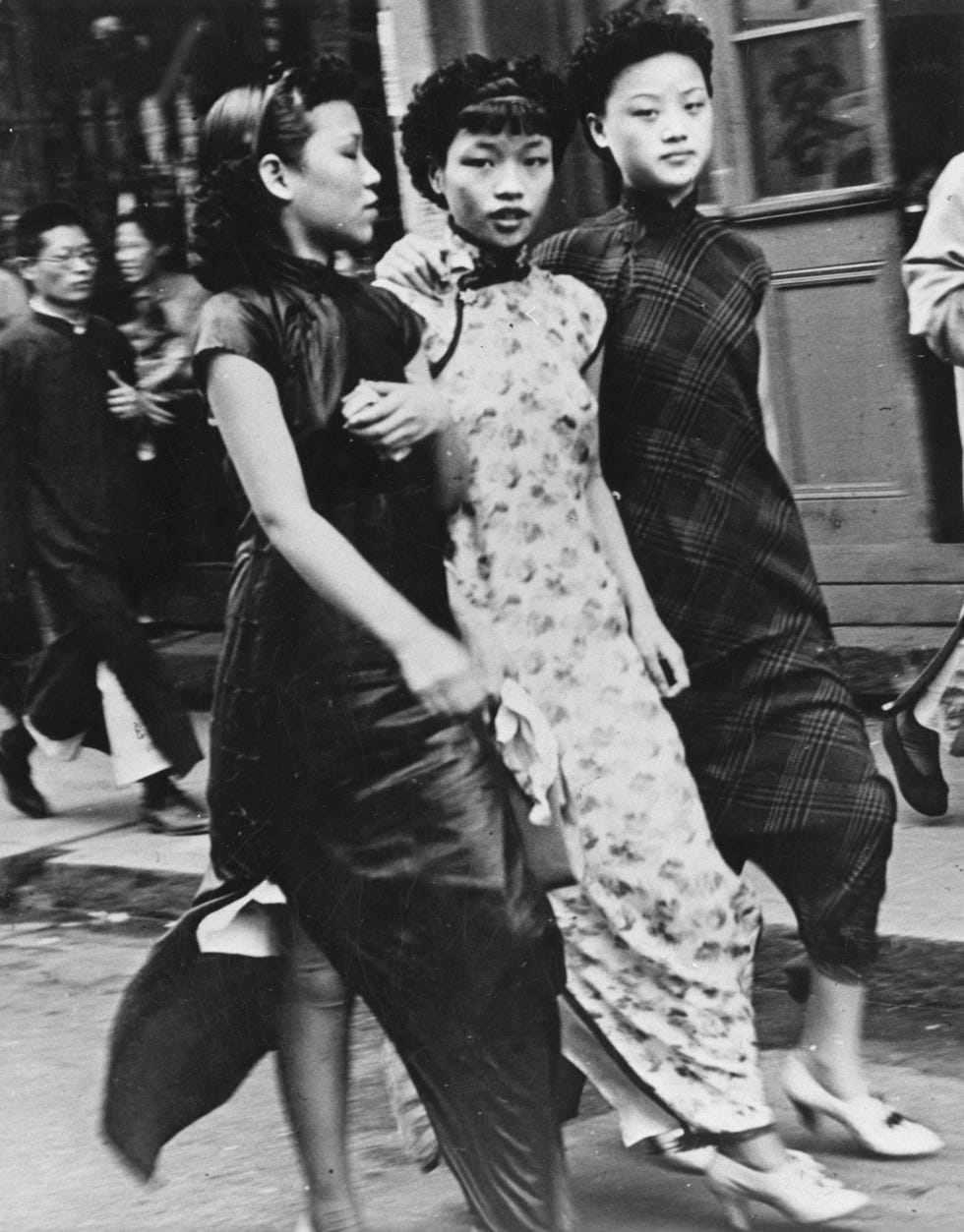

The silhouette changed over time, but the meaning behind the qipao remained constant: women’s liberation and the evolvement of self-perception. In the 1940s, the adoption of bras in Hong Kong and Taiwan further transformed the dress, with dressmakers using darts to shape the bodice and emphasize the bust, according to Finnane. From 1949 until the 1970s, the qipao lost popularity, as many perceived it as a relic of outdated Chinese traditions at odds with the drive for modernization. People gravitated towards more functional, Western-inspired attire like jackets and trousers. Amid the upheaval of the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s, however, numerous tailors sought refuge in Hong Kong, where they blended traditional Chinese aesthetics with Western influences, and so the dress flourished in the then-British colony.

The qipao made another return to the fashion world in the ’90s and early 2000s when fast fashion brands capitalized on traditional Chinese prints and silhouettes. Brands like Forever 21 produced so-called “mandarin-collared” shirts with machine-stitched dragons and Chinese characters that don’t form actual phrases. In 2002, Abercrombie & Fitch faced criticism for selling T-shirts with racial slurs and images, such as “Wong Brothers Laundry Service—Two Wongs Can Make It White.”

Although the qipao has historically been associated with the women’s liberation movement, reflecting evolving perceptions of women’s bodies as they broke free from traditional roles, some brands disregarded its rich history and the struggles of oppression endured by Chinese women. These companies often commercialized and fetishized traditional attire, disregarding its deeper meaning. In 2019, PrettyLittleThing’s collaboration with British girl group Little Mix received backlash from the API+ community for culturally appropriating traditional Chinese attire. The collection, which featured crop tops and mini skirts in dragon patterns, was described as “oriental” by the brand.

Ruohan Song, a traditional Chinese fashion influencer and qipao collector, tells ELLE.com that Chinese women in the U.S. still face stereotypes and sexualization because of the way those who wear qipaos have been portrayed in the media. Asian female characters who wear them are either seen as intimidating (like the “Dragon Lady,” inspired by the female villain from the comic Terry and the Pirates), as delicate and submissive, or as hypersexualized, reinforcing narrow and outdated stereotypes. “When we [consider] the qipao in the U.S., people often think of a dress with a high slit that reveals thighs and buttocks with a cut-out in the front, which is drastically different from the traditional dress,” Song says. “When you search on Amazon, the descriptions and pictures are horrifying. I feel disheartened that only a handful of people knew the history behind this dress.”

In 2017, a heated debate broke out on social media over a non-Chinese high school student who posted pictures of herself wearing a red qipao to prom. The question of whether someone who is not Chinese could wear the traditional dress went viral, but Song feels it is more complex than that. “It’s important to understand that the perception of the qipao is deeply ingrained in society, and it’s not the fault of those who wear them,” she says. “Fetishization and appropriation are not desirable, but if, for example, I had an American friend who had studied the history behind the dress and wanted to wear one with respect and understanding, I would find that completely acceptable. It’s important to approach this with respect and an informed attitude.”

Guo agrees that educating people about the garment’s historical and cultural significance is crucial to preventing cultural appropriation and misrepresentation. “Like the kimono in Japan, the qipao has also been used as a tool to sexualize and objectify women, perpetuating stereotypes. The misinterpretation diminishes the achievements of Asian women and makes them more vulnerable,” she says.

To encourage more women to appreciate the beauty of the traditional qipao, she works with a tailor in Shanghai to create new designs inspired by vintage styles to sell. Currently, her Manhattan shop has over 30 designs, each available in seven sizes. “It’s not true that only slim women can wear qipao. Almost everyone can find their perfect dress here,” says Guo.

For Guo, the qipao represents more than just a fashion statement. She sees it as a bridge to the past, connecting her to the women who wore these dresses to make a statement. “I could feel their liberation as women, their struggles to challenge societal norms, and their appreciation for their bodies and identities,” Guo says. She believes Hong Kong’s fashion history deserves more recognition, which is why she named her store “Xiangjiang Vintage” after the Mandarin term for the city.

Many fashion brands, both in China and the U.S., are now embracing “modern Chinese style” by incorporating qipao-inspired buttons and high collars, but Guo believes it’s essential to stick to traditional designs when crafting qipaos. Traditional qipao options in the U.S. are very limited, making it a challenge to change the public’s perception of the dress, which is why she is committed to preserving her culture.

As Guo walks to a coffee shop in her qipao, I—a Chinese woman living in the U.S.—have to wonder if she has ever felt scared of being “unapologetically Chinese” on the street, considering the uptick in hate crimes over the last few years. “I feel liberated in qipao,” Guo says. “By wearing it daily, I want to encourage more Chinese women to find their identities and sense of belonging through the dress. If I can proudly wear the dress, then we could move beyond the anti-Chinese racism and find who we really are.”

The post The Feminist Roots of the Chinese Qipao appeared first on Patabook Fashion.