The phenomenon of bioluminescence first evolved in animals at least 540 million years ago, a new study has discovered.

The first animals to ever glow in this way were marine invertebrates called octocorals, the study conducted by researchers at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History reported.

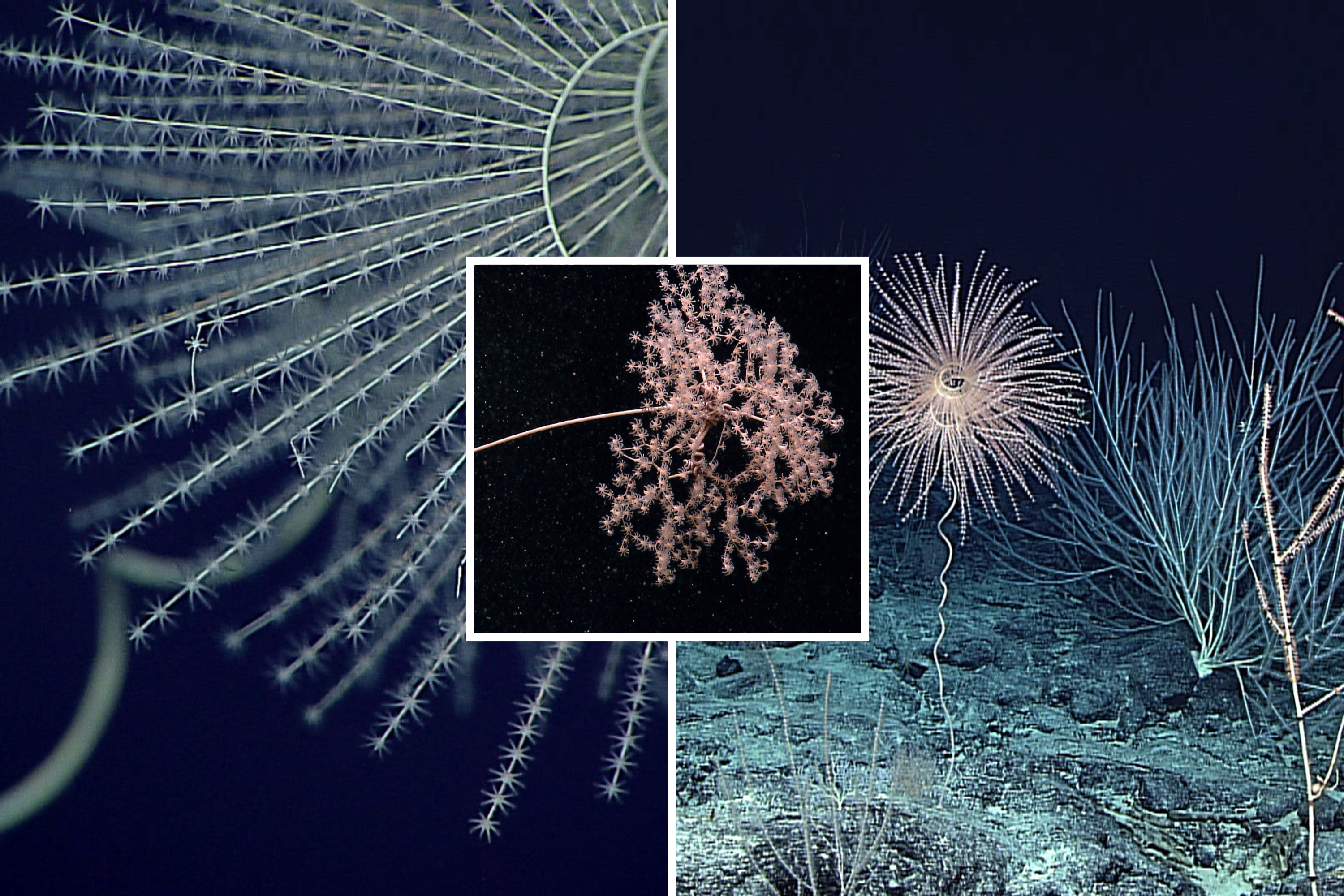

Bioluminescence refers to the glow that some marine organisms can produce. The glow can make these animals look like they are electrical, giving of a beautiful colored light. The phenomenon is caused by a light-producing chemical reaction within an organism’s body.

Before now, scientists thought that the strange phenomenon first appeared in marine crustaceans called ostracods about 267 million years ago. This was never certain, as the strange ability is hard to study. These new findings, however, suggest that it is actually a much older trait.

“We predicted that bioluminescence was an ancient trait, but we did not assume the ancestor of all octocorals were bioluminescent, so that was exciting! We now know that this chemical reaction evolved around the time that life on earth rapidly diversified, over 540 million years ago,” lead author Danielle DeLeo, a museum research associate and former postdoctoral fellow, told Newsweek.

NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Deepwater Wonders of Wake / NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition 2013 / NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana

Nobody really knows why the trait first evolved in animals. Scientists do know however, that the trait can assist animals in communication, camouflage, courtship, and hunting. The findings could help inform scientists into why animals evolved with this trait in the first place.

To reach these new findings, the researchers looked back on the history of octocorals and how they evolved. This group of organisms includes soft corals, sea fans, and sea pens. They usually only glow when they are disturbed by an external force, or bumped in some way. This has always posed a mystery to scientists, as the real reason for their bioluminescent ability remains unknown.

“We wanted to figure out the timing of the origin of bioluminescence, and octocorals are one of the oldest groups of animals on the planet known to bioluminescence,” DeLeo said in a statement. “So, the question was when did they develop this ability?”

The researchers used two fossils to map when octocorals split from other ancestors, and adapted their luminous ability.

They used various statistical methods for their research and all found that 540 million years ago, these organisms were bioluminescent. This was 273 million years before ostracods developed the ability.

“Our study presents the oldest published record for the appearance of bioluminescence on earth, and more than doubles the previous timeline for when bioluminescence first appeared. Our findings support bioluminescence, and light signaling in general, as one of the earliest forms of communication on earth,” Deleo told Newsweek.

“Some animals that could detect light evolved during a similar time during the Cambrian. Thus, our research hints at the possibility that interactions involving light occurred between species during a time when animals were rapidly diversifying and occupying new niches.”

The fact that bioluminescence has been maintained for so long also suggests that “it must have contributed significantly to their overall fitness.”

As it is commonly found in deep water corals, its luminous ability likely allowed it to become more diverse throughout these dark waters.

“Now, we know that bioluminescence is a critical form of communication for many animals across the tree of life and particularly for those that occur in the deep sea,” DeLeo said.

Following these findings, scientists are now looking into which octocorals still have bioluminescence and which do not. There are over 3,000 species of octocorals, meaning this will take a while. But it will help inform them further of the mysterious evolutionary trait, and why it came to be. Aside from this, the study offers more context into the evolution of these marine organisms.

“We would like to test the bioluminescent predictions from our study to confirm whether various animals possess this trait,” DeLeo said. “To that end, we hope to develop a genetic test for bioluminescence based on the major enzyme involved in the reaction, luciferase, which is inherited. This will enable easier and less invasive investigations of bioluminescence in harder-to-access environments, like the deep sea.”

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about bioluminescence? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.