A film five years in the making about the poisonous effects of movie fame on the young, this fascinating but dismally depressing Swedish documentary is well worth seeing, but never fully escapes the feeling that it’s all been seen before. It’s a chronicle of the tortured life of Björn Andresen, the Stockholm teenager legendary Italian director Luchino Visconti brought to overnight international stardom at the age of 15 in the coveted role of Tadzio opposite Dirk Bogarde in the homoerotically charged 1971 film version of Death in Venice. In the novel, author Thomas Mann described Tadzio as a human version of a Greek sculpture—”with an expression of pure and godlike serenity.

|

THE MOST BEAUTIFUL BOY IN THE WORLD ★★★ |

With all this chaste perfection of form, the observer thought he had never seen, either in nature or art, anything so utterly happy and consummate.” Yet 50 years after the film’s premiere, this documentary by Kristina Lindstrom and Kristian Petrie reveals “happy” and “consummate” were two words about Tadzio that did not describe the result of fame on the boy who played him. Watching the toxic years of misery and the tricks of fate that destroyed Björn Andresen, I kept thinking about the tragic life of Jean Seberg after Otto Preminger “discovered” her for the title role of Saint Joan.

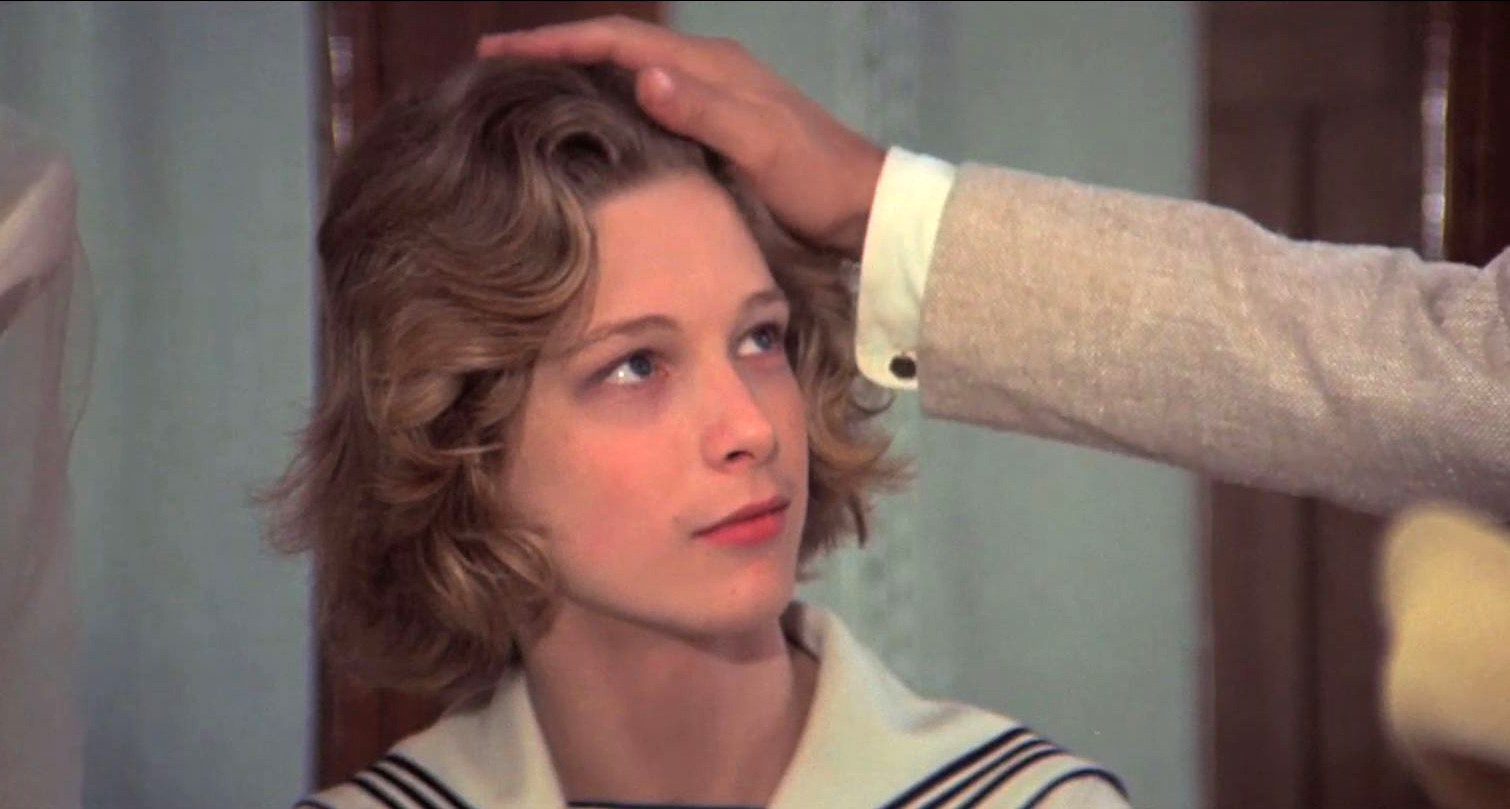

The directors begin their trajectory on a bitterly cold February day in 1970, when the legendary, openly gay Communist director Visconti arrived in Sweden searching for beauty. The boy he selected after he walked around a hotel room with his half-naked torso was exactly what Visconti was looking for—pale, bland, innocent and beautiful. Björn had no experience and little knowledge or understanding of the subject matter—an intellectual pursuit of youthful perfection that can only end, once found, in death. To avoid any hint of sexuality, Visconti forbid any personal contact between Björn and the homosexual crew members, leaving the boy isolated, alone, and more confused than ever. (This insistence on pure love without emotion between an aging composer, played by Dirk Bogarde, and the boy was the film’s ultimately cold, dispassionate downfall.) In the voice of the grown Björn, he received no direction except four words—“Go! Stop! Turn around! and Smile!” The result was a vacuous performance that enchanted neither critics nor audiences, but the director tagged Bjorn “the most beautiful boy in the world” and at the 1971 Cannes Film Festival the label stuck, haunting Björn forever.

The ensuing years illustrate a life created exclusively out of publicity. There is footage of the London premiere, attended by the Queen and Princess Anne. Hordes of journalists, sacks of fan mail, and a consuming attention relished only by the ambitious grandmother who raised him, are described by the elderly Björn as “a living nightmare.” He wanted to escape, but Visconti signed him to a three-year contract, in essence owning his face, with no plans to ever use him in another film. To further exacerbate matters, the director told the crew “We’ve got our film now. So you can do what you want with the boy.” They took him to gay bars, plied him with alcohol until he passed out, and turned him into an alcoholic. In New York fans waved streamers from rooftops and chased him with scissors to cut off locks of his hair for souvenirs. He moved to Paris, where he was kept for years by older men who showered him with expensive dinners and gifts and paid his expenses. The film is annoyingly vague about what Björn did to pay them back, but stops short of calling him a prostitute. Today the stress and abuse show. Thin, bony, lined with wrinkles and hirsute, with shoulder-length white hair and beard, he looks older than 65 and lives in squalor. We see his landlords trying to evict him for a filthy apartment and him leaving the gas on, endangering the entire building. Seeking clues to his identity, he never finds out anything about his father, but discovers newspaper clippings about the body of the mother who abandoned him, dead in the woods in 1966, her head resting on a root. This leaves him more depressed than ever—and the viewer, too.

It gets worse. He believes that he rolled over in an alcoholic stupor and accidentally killed his only son. His grown daughter hasn’t seen him in 12 years. His girlfriend, who tried to help him pull his life together, dumps him, calling him a “pig” and a “bloody bastard.” He has nothing but regrets about the past and no future with any promise. We’re left with the inescapable impression of a man who is lost, despondent and forever undefined.

Filmed in Stockholm, Paris, Tokyo, Italy and Budapest, the movie is almost as gorgeous to look at as Death in Venice, but eventually, nearly as much of a bore. Writer-directors Lindstrom and Petri clearly try to make a point about how too much too soon can make a destructive impact on a young actor’s life, but blaming it all on Death in Venice is a stretch that is not always convincing. It’s pretty obvious that Björn Andresen’s pathetic downfall is nobody’s fault but his own. All the most beautiful boy in the world wished for was for his beauty to pay off. This film makes it clear that sometimes it’s better to wish for a wart instead.

Observer Reviews are regular assessments of new and noteworthy cinema.