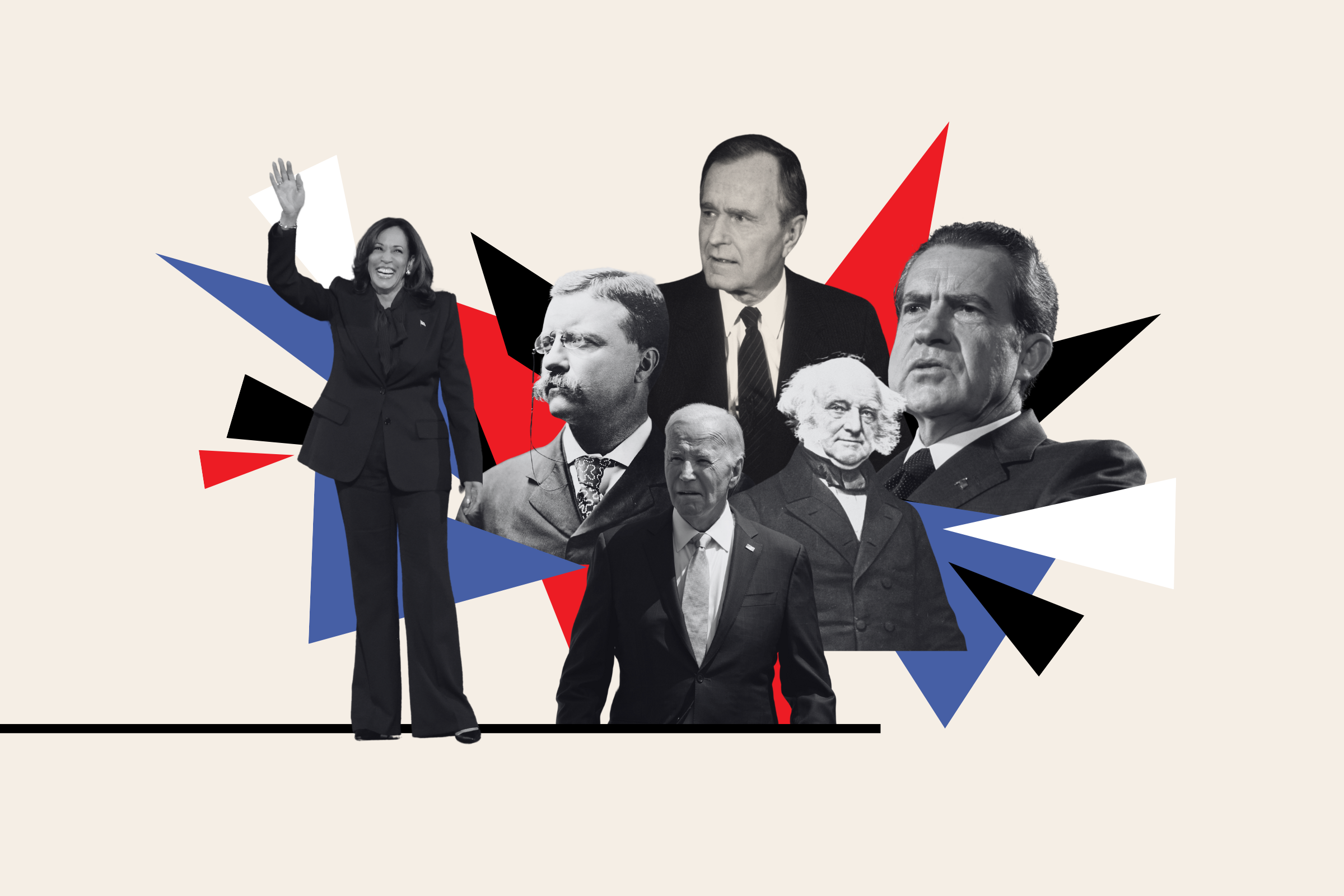

As Vice President Kamala Harris gears up for the upcoming presidential election, the historical trajectory of vice presidents who have sought the nation’s highest office provides compelling context and insights into her run.

Historically, while the vice presidency can be a springboard to the Oval Office, its success rate varies. Only one sitting vice president since 1836 has run for president and won: George H.W. Bush, in 1988.

Harris, the first woman, Black and South Asian vice president in U.S. history, faces a unique set of challenges and opportunities.

The Most Insignificant Office

The nation’s first vice president, John Adams, is said to have once described the job as “the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived.”

Under the original U.S. electoral system in place from 1789 until 1804, electors cast two votes for president and the candidate who came second was appointed vice president. Adams was the runner up to George Washington in the country’s first ever election, and received the second-highest number of votes again four years later. In 1796, he became the first vice president to run for and win a presidential election, beating Thomas Jefferson, who became Adams’ vice president. Jefferson beat Adams in the following election in 1800, becoming the second person to win the presidency after serving as second-in-command.

Adams was actually knocked into third place that year by Aaron Burr, in the first example of a U.S. election with formal tickets: electors in support of Jefferson also voted for Burr, while those in support of Adams also voted for Revolutionary War hero Charles C. Pinckney.

The U.S. has been voting for presidential and vice presidential tickets ever since.

A Heartbeat Away From the Presidency

In total, 15 vice presidents out of 49 have gone on to become president either through the death or resignation of the president, or by winning an election in their own right after their vice presidential term ended. These are:

- John Adams: vice president 1789–1797, became president in 1797 after winning election against Thomas Jefferson.

- Thomas Jefferson: vice president 1797–1801, became president in 1801 after winning election against the incumbent Adams.

- Martin Van Buren: vice president 1833–1837, became president in 1837, succeeding his old boss, President Andrew Jackson after an election with a crowded field of candidates.

- John Tyler: vice president 1841, became president after William Henry Harrison’s death but was later expelled from the Whig party and dropped out of the 1844 election as a third-party candidate, endorsing eventual winner James K. Polk, a Democrat.

- Millard Fillmore: vice president 1849–1850, became president after Zachary Taylor’s death but did not win his party’s nomination as its presidential pick in 1852.

- Andrew Johnson: vice president 1865, became president after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination but did not gain his party’s nomination in 1868 after being impeached and nearly removed from office, among other issues.

- Chester A. Arthur: vice president 1881, became president after James A. Garfield’s assassination but did not win his party’s nomination for president in 1884.

- Theodore Roosevelt: vice president 1901, became president after William McKinley’s assassination. He went on to win the election in 1904, but decided against running for a full second term of his own in 1908.

- Calvin Coolidge: vice president 1921–1923, became president after Warren G. Harding’s death and won the election in 1924. He decided against running for a full second term in 1928, writing later in his memoirs that “the Presidential office takes a heavy toll on those who occupy it and those who are dear to them.”

- Harry Truman: vice president 1945, became president after Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death. He won his own election in 1948 but opted not to seek a second term in 1952 amid low approval ratings.

- Lyndon B. Johnson: vice president 1961–1963, became president after John F. Kennedy’s assassination. He won a landslide victory in 1964 but shocked the country when he announced he would not run for re-election in 1968.

- Richard Nixon: vice president 1953–1961, became president in 1969 after defeating sitting Vice President Hubert Humphrey. Nixon had previously run for president when he was vice president in 1960, losing to then Massachusetts Sen. John F. Kennedy.

- Gerald Ford: vice president 1973–1974, became president after Richard Nixon’s resignation. He pardoned Nixon for any crimes the former president might have committed in office and later lost the 1976 election to former Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter. Ford is the only person in U.S. history to serve as vice president and president without being elected to either office.

- George H. W. Bush: vice president 1981–1989, became the first sitting vice president since Van Buren to win a presidential election, defeating Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis.

- Joe Biden: vice president 2009–2017, became president in 2021 after defeating President Donald Trump. He did not seek to run for president in 2016, citing the death of his son as the reason.

Biden’s announcement in July to not seek re-election sets up Harris as potentially the next member of a small club of sitting vice presidents who have gone on to win a presidential election.

Or she could join the slightly longer list of six sitting vice presidents who tried and failed in their bids for the top job, including fellow Democrats Hubert Humphrey and John Nance Garner.

Alex Wong/Getty Images

The Understudy

Matt Dallek, Professor of Political Management at the College of Professional Studies, told Newsweek that it is tough to place Harris in relation to past vice presidential bids, as the situation surrounding her campaign is so unique.

Dallek said: “One challenge incumbent VPs face is that they are trying to keep their party in power after it has spent four or eight years in the White House. Al Gore lost after being VP for eight years, Richard Nixon was defeated in 1960 after two terms as [Eisenhower’s] VP, but George H.W. Bush won in 1988, which was something of an exception.”

“To the extent that a pattern exists that is applicable to Harris, I’d point to moments when presidents suddenly withdraw or die in office, and the VP is thrust into either the presidency or the presidential nomination.”

“It’s hard for a VP to win the White House after serving eight years as the understudy, but it is easier when circumstances thrust the VP into the spotlight, as has been the case with Harris.”

Drew Angerer/Getty Images/Hulton Archive

Pros and Cons

Experts are skeptical of how useful the spotlight of the vice presidency is for prospective presidents.

“Serving as vice president confers tremendous advantages stemming from being the second-highest office holder, especially support within one’s own party and national name recognition, though this can cut both ways if that national perception is negative,” said Professor William Hurst, co-director of the Cambridge University Centre for Geopolitics, in the U.K.

It was quite common in early U.S. history for vice presidents to become president after serving in the former role, but between Martin Van Buren in 1836 and George H.W. Bush in 1988, no sitting vice president who received their party’s nomination won an election. Some didn’t even get the nomination. Presidential historian Laura Smith said that the most electorally successful vice presidents who won election were the ones who came into the office due to the death of their president, which set those men up for the next election.

“In the 20th century, being vice president became the most likely stepping stone to the presidency,” Smith told Newsweek. “This includes following two presidential assassinations that brought Theodore Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson to the Oval Office, and Franklin Roosevelt’s death that led to Harry Truman’s ascension to the presidency.”

Theodore Roosevelt and Johnson—along with Calvin Coolidge, who became president after the death of Warren G. Harding—all won landslide victories in their own right after finishing their predecessor’s terms, with more than 54 percent of the vote. Truman delivered an electoral upset, defeating the heavily favored New York Gov. Thomas E. Dewey with 49.6 percent of the vote.

Underwood Archives/Getty Images

“A Pitcher of Warm Piss”

Things didn’t work out so well though for the vice presidents of Theodore Roosevelt, Johnson or Truman. Charles W. Fairbanks sought the nomination in 1908 but his boss backed Secretary of War William H. Taft. Alben W. Barkley withdrew from the Democratic primary race in 1952 amid concerns over his age (he was in his seventies) and Hubert Humphrey couldn’t shake his ties to Johnson’s unpopular foreign policies in 1968, losing in the general election to Nixon.

Like Hurst, Smith also identified the vice presidency as a double-edged sword, that could bring significant baggage from the administration they worked under.

“Former Vice President John Nance Garner warned Johnson in 1960 that ‘the vice presidency isn’t worth a pitcher of warm piss,’ so the benefit of the job is [definitely] debatable. The role certainly provides executive experience and national visibility but a vice president is also tied to the administration they serve, for better or worse.”

For Harris, this could include Biden’s unpopular foreign policy decisions over Afghanistan, or unpopularity with younger voters over his administration’s approach to the war in Gaza.

Dallek told Newsweek that avoiding these unpopular issues will be key to a November victory, saying: “Ideally, Harris wants to benefit from elements of Biden’s agenda that are popular with the voting public—such as infrastructure, the CHIPS Act, millions of jobs created, declining crime rates, and more—while avoiding the negative stigma attached to some of the more unpopular parts of Biden’s presidency, like inflation and the border situation.

“So far, she seems to be defining herself on her own terms, running a different kind of campaign on distinct issues from Biden, while using her time in office to show the American people that she has the knowledge and experience to lead on day one.”

Do you have a story we should be covering? Do you have any questions about Kamala Harris and the vice presidency? Contact LiveNews@newsweek.com.