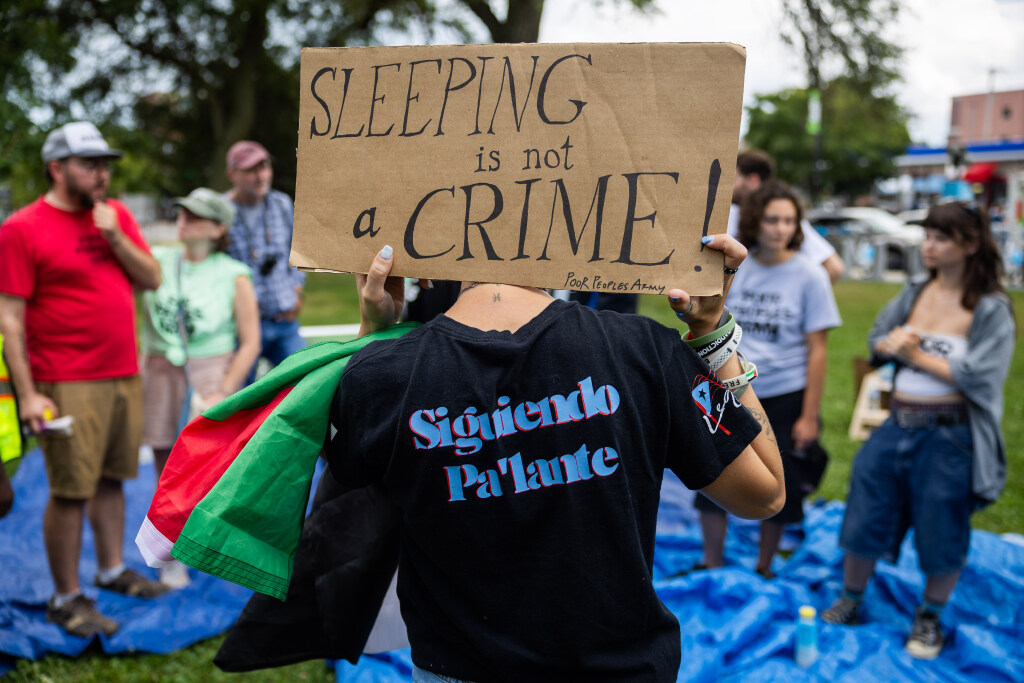

In anticipation of next week’s Democratic National Convention, a Philadelphia-based group that advocates for homelessness and poverty-related issues, arrived at Humboldt Park on Saturday, prepared to set up encampments that would call attention to homelessness.

But upon arrival, the demonstrators—many who had walked the 90-mile trip from Milwaukee, where they marched on the Republican National Convention—were met by Chicago police, who said the group would not be allowed to pitch any tents that would add to the number of tents belonging to unhoused people already set up throughout the park.

Police officials at the park Saturday said it is the group’s First Amendment right to remain in the park, so long as they don’t set up their tents.

The arrival of the Poor People’s Army was only the beginning of a whirlwind weekend where thousands, delegates and demonstrators, were expected to descend on the city for the DNC, where Vice President Kamala Harris was expected to accept her nomination for president later in the week.

The group plans to march on Monday, the first day of the Democratic National Convention, from Humboldt Park to the United Center.

With the pro-Palestinian protests of the spring looming in the recent past, the police have expressed confidence that they are prepared to handle whatever ensues.

Expressing their grievances and concerns about the order to stand down on setting up their tents, the group held a news conference Saturday afternoon where members called on elected officials to prioritize ending homelessness and poverty. They also support causes like an end to U.S. military aid to Israel.

“We’re delegates with no money,” Cheri Honkola, organizer and co-founder of the Poor People’s Army, said about their goals for the encampment and protest. “We do it because we seriously care about what’s going on, and we can’t take it anymore.”

The group of about 20 protestors, made up of currently and formerly homeless individuals, said they expect their numbers to grow before they march on Monday with supporters from the city and beyond.

This year, the group placed special importance on the U.S. Supreme Court’s June decision that allowed cities to enforce bans on homeless people sleeping outside. Since the decision, states like California have undertaken sweeping crackdowns on homeless encampments.

Chicago, too, recently cleared several homeless encampments, though Mayor Brandon Johnson later denied statements made previously by his administration attributing homeless encampment clearings to the DNC.

As of January 2024, the city estimates there are about 5,000 unhoused people in Chicago, excluding the more than 13,000 new arrivals being housed in shelters, according to its 2024 Annual Report on Homelessness.

Despite the orders not to pitch their tents at the park’s southern edge, the Poor People’s Army said they don’t intend to leave. As an afternoon rain shower hit the park, the group sheltered under tarps they had brought, some donning trash bags as makeshift rain jackets.

“Can we stay in the park if we don’t put up a sign?” Honkola asked. “If you put up a sign that says you’re against poverty, hunger and homelessness, then you can be run out of the park by police.”

Saturday’s gathering also saw disagreements between encampment organizers and local alderpeople who said they only recently learned of the planned encampment though organizers claimed members passed out fliers and spoke at community meetings months in advance.

Ald. Jessie Fuentes, 26th, whose ward includes Humboldt Park, showed up to the park in anticipation of the demonstrators’ arrival. She said she didn’t know about the plans for an encampment until a few days ago and cited “safety and security concerns” in the park due to the current homeless encampments. “We are here to be the intermediary so there is no contact with the police,” Fuentes said. “I didn’t call the police here.”

Fuentes said she was willing to suggest alternate locations nearby for the group to set up their encampment, but the group was unwilling to consider the proposal.

“We didn’t march all the way from Milwaukee to be silenced here in Chicago and be invisible,” said Galen Tyler, a formerly homeless member of the Poor People’s Army, said of the proposals to move the encampment elsewhere.

The group, which has been marching on Republican and Democratic conventions since 2000, received a permit to march at the DNC by an apparent accident.

The group’s marching route has been the subject of dispute, as the route they won in February takes demonstrators past the United Center and within the Secret Service’s security perimeter. They said on Saturday that they plan to carry on with their original plan in hopes of making their cause publicly visible.

Tara Colon, a formerly homeless mother and member of the Poor People’s Army, noted the increase in homelessness post-COVID-19, saying that the issue needs to be prioritized as a nationwide issue – at the DNC and beyond.

“No one’s talking about it,” Colon said. “That should be the number one thing that they should be talking about in the Democratic Convention and in the Republican Convention.”

Originally Published: