The Boston Globe

When GBH laid off nearly three dozen workers last month, chief executive Susan Goldberg cited flat revenue and rising costs that left one of the nation’s largest producers of public media in the red.

Left untouched were the high salaries received by the 16 top executives at the station, who together earned $5.9 million last year in total compensation (GBH eliminated year-end bonuses for all staff, but did not cut base compensation). Their high pay — nine earned more than $300,000 in base compensation each last year, the nonprofit’s records show — has prompted criticism among current and former employees about the organization’s choices in confronting a budget shortfall of $7 million for its core business.

“I’ve spoken to a bunch of higher-paid people here since the layoffs,” said Jim Braude, co-host of GBH’s popular “Boston Public Radio” show, who records show earned $491,428 last fiscal year, making him one of the organization’s top-paid employees. “We all would have been willing to take pay cuts to save costs if we had been asked.”

(Braude’s base compensation is now $344,850, according to a term sheet he provided to the Globe, down from the $464,031 he earned in the tax filing. He said the difference reflects the loss of a salary from hosting “Greater Boston,” which he stepped away from in December 2022.)

To meet its budget goals, GBH laid off 4 percent of its workforce and suspended three television programs it said had low viewership, terminating six workers on those shows. Many had salaries ranging from $50,000 to $65,000, according to interviews with current and former employees.

“GBH can claim this is a financial decision all they want, but there is always a human impact,” said Zoe Mathews, a senior radio producer at GBH and a steward for the union that represents some newsroom employees. “You don’t need to lay off entire production teams for financial gain.”

In a statement, a GBH spokesperson said the decision to lay off staff and cut programming was part of an effort to transform GBH “to be even more impactful and financially sustainable.”

“While driven by financial headwinds, layoff decisions were also made in a manner to best serve the business going forward,” the statement said. “Each decision was specific to the individual role. Some eliminated roles supported suspended programs, while others became unnecessary when departments or operations were consolidated.”

The spokesperson added that GBH’s employee and executive compensation is in line with the industry and it is “committed to offering fair compensation to its employees.”

The organization underwent a review of its compensation policies over the past four years, the spokesperson said, and made adjustments where salaries were not competitive. Salary structures are updated annually.

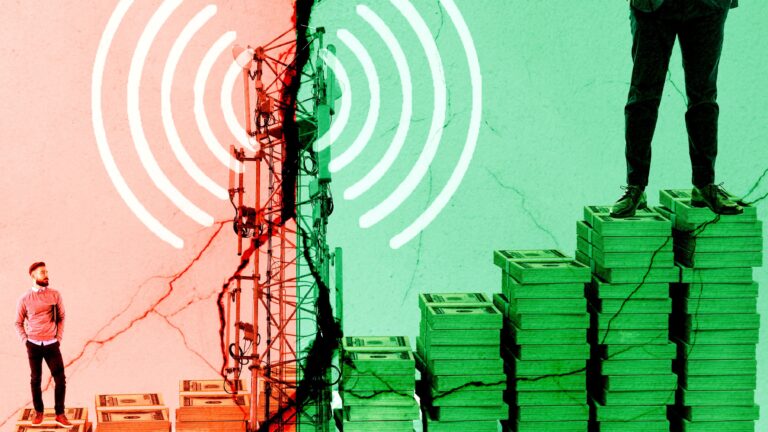

The financial challenges at GBH and other public media outlets across the country have raised questions about the viability of traditional business models that have long supported legacy media organizations like GBH. They also have put a spotlight on compensation and the divide between decision-makers and rank-and-file employees responsible for producing television programs, radio shows, and articles. Often, it is the latter who are laid off when a media organization makes cuts.

“CEOs need to be accountable for the decision-making,” said Gabe Schneider, co-executive director of The Objective, a nonprofit outlet that focuses on power and inequity within media. ”And that means that if there is a downturn, they need to cut their salaries significantly in favor of showing the staff that they care, and that they’re trying to do as much as possible to prevent layoffs.”

Some employees hope that the financial challenges present an opportunity to rebuild GBH into a sustainable organization.

“We need to come up with a better business model,” one GBH employee said. “I don’t know what a CEO should make, but I know people at the bottom should be making much more.”

While details on compensation at media outlets are often kept secret, nonprofit organizations like GBH file annual reports with the Internal Revenue Service that require them to disclose the income of top-paid staff.

The largest producer of PBS content, GBH runs a far larger operation than most public media organizations. It generated nearly $270 million in revenue last fiscal year, has more than 800 employees, and produces dozens of programs for radio and TV, plus podcasts, closed captioning services, and educational content. Though it’s hard to compare GBH with others, since it has few peers that produce a similar breadth of programming, its chief executive has been one of the highest paid CEOs compared to those at other large nonprofit media organizations.

In fiscal year 2022, former GBH chief executive Jonathan Abbott took home $754,310 in compensation, according to public tax filings. That was more than the chief executives of NPR, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, ProPublica, and WNYC in New York. Still, his compensation was less than that of the CEOs of PBS, WETA in Arlington, Va., and WNET in the New York area.

While Abbott’s compensation exceeded peers at many other public media organizations, so did GBH’s overall budget. A GBH spokesperson emphasized that Abbott’s compensation accounted for a smaller percentage of the organization’s revenue than was true for his counterparts at WETA, WHYY, WNYC, and WNET. Abbott, who left GBH in 2022 and made $800,000 last year, did not respond to a request for comment.

Current chief executive Goldberg, who joined GBH in December 2022 as the first woman to lead the organization, earns a salary of $620,000, a GBH spokesperson said.

The salaries of rank-and-file members of the newsroom are not public, but a union that represents some newsroom employees sets minimum salaries in its contract that range from roughly $29,000 to $73,000. A contract extension in 2023 raised those minimums by 5 percent.

A GBH spokesperson said that the organization “rarely” pays the minimum salary, and added that the average union salary is $72,764 and the average non-executive salary is $100,843. Across GBH, 29 percent of employees are represented by a union.

From 2017 to 2023, Abbott’s annual compensation grew by roughly 35 percent. During the same period, the minimum union salary for associate producers and reporters at GBH only rose 19 percent, according to publicly available union contracts from CWA 1400 Local, which represents some GBH employees. For example, the minimum salary for associate producers only increased to $38,284 from $33,880.

Five current and former GBH employees who spoke to the Globe were disappointed by their former CEO’s compensation and dismayed that many of the laid-off staff were lower-level employees. The employees spoke on the condition of anonymity out of fear of retribution for speaking publicly.

“Us journalists at the bottom of the totem pole are the ones making the stuff that people watch, the stuff that people read, the stuff they’ve listened to,” said one worker who was laid off.

GBH announced last week that it was laying off 31 employees and suspending production of three television programs: “Greater Boston,” “Talking Politics,” and “Basic Black,” the last of which was the nation’s longest-running public television program focused on the concerns of people of color. The layoffs last week included 11 employees in the GBH newsroom, the Globe previously reported, which represents about 11 percent of its staff.

Goldberg first warned employees of potential layoffs in March, when she and other executives disclosed a shortfall brought on by rising costs from medical benefits, travel, events, and marketing as revenue remained flat. They also announced the elimination of year-end bonuses across the organization.

In 2009, when faced with financial challenges amid a recession, GBH slashed executive compensation by 5 percent as one measure to cut costs. It later laid off at least 33 employees, according to Boston magazine.

Some former employees spoke of the difficulty of living on the salaries they earned at GBH in Boston, one of the country’s most expensive cities where many people struggle to get by.

“It was just not a livable Boston wage,” said one laid-off employee in her 30s who made less than the average union salary. To get by, the employee, who worked on video production, lived with her parents and had to advocate multiple times for a raise.

Another former GBH employee who also worked on video production said the first offer she received was lower than $50,000, which would have meant halving her previous salary at a for-profit news organization. Her manager secured her a higher salary, but she still had to work a second job on weekends during her time at GBH to make ends meet.

“I know I’m not the only one who felt I was underpaid,” she said.