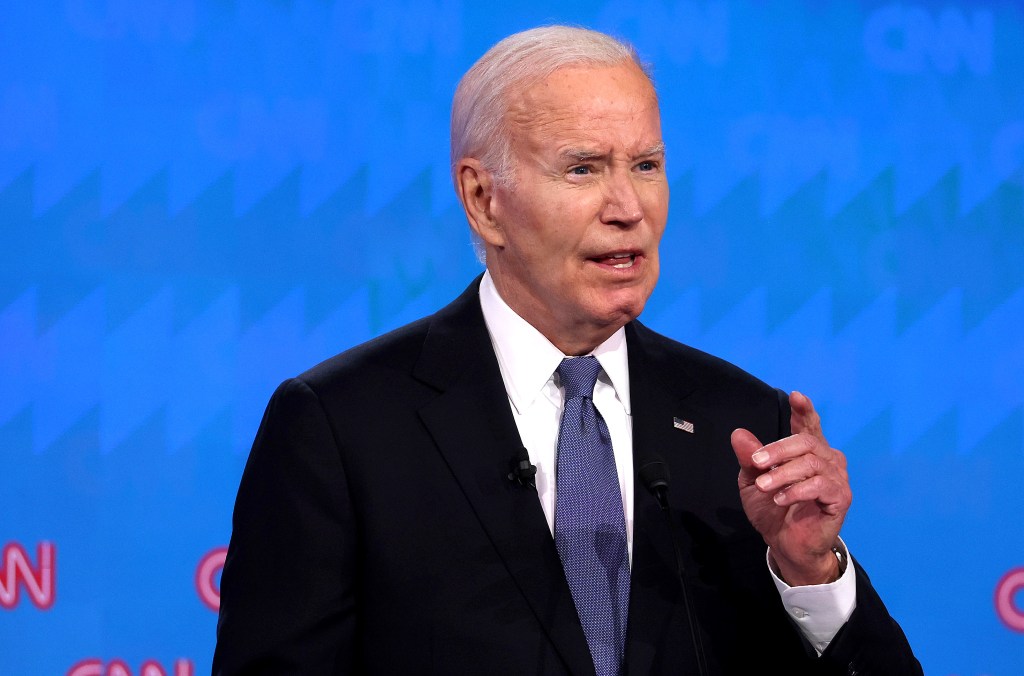

I love Joe Biden. For his accomplishments as senator and president, for his gaffes (yes, passing Obamacare was a “big f—ing deal”), for his steadfast devotion to his children, but mostly for his persistence and grace in the face of unfathomable personal loss. He cares deeply, and that matters to me and to millions of voters.

I didn’t always feel this way about Biden. For many years, I thought he was an arrogant, vacuous boor from my personal experience with him.

In the spring of 1978, Biden was finishing his first Senate term. He introduced a floor amendment to the Justice Department appropriations bill that would have precluded Justice from enforcing a federal court order that mandated a metropolitan school busing plan for New Castle County in Delaware, his home state. The order required busing students from Wilmington into other communities in the county, and vice versa, to rectify gross, discriminatory racial imbalances in the Wilmington and suburban schools.

My 74-year old but still razor-sharp boss, Jacob Javits, was managing the Senate debate on the civil rights provisions of the funding bill and was the lead opponent of Biden’s amendment. I was Javits’ aide on education policy and he asked me to staff him for the debate, which meant that I would be sitting with him on the Senate floor, passing him notes, whispering in his ear, helping him buttonhole and consult with other senators, pouring his water. Pretty heady stuff for a kid of 25.

Biden offered his amendment and shouted his arguments for it. Javits calmly and articulately rebutted. Biden grew angrier, red-faced and louder. He left his rostrum and stood within inches of Javits, shouting and pointing his finger at him. That was a gross violation of Senate protocol — a point of personal privilege — for which Biden could have been cited by the presiding officer.

Javits stood and listened calmly and didn’t bother to ask for a ruling from the chair. I sat by him, cowering. After about an hour, as the debate was ending, Javits sat down next to me and whispered “what a callow jerk.”

Biden’s amendment was defeated narrowly, but a similar rider to the HEW funding bill that prohibited school districts receiving federal funding from using those funds to bus students passed later that year. Busing as a remedy for racial segregation of schools was pretty much over.

Fast forward to 1984. I was the University of Pennsylvania’s Washington lobbyist and rode Amtrak about twice a week from Philly to D.C. and back. As he commuted daily from and to Wilmington, Biden was often on my train and sometimes in my carriage. Sometimes Biden would get to Union Station for the train north just before departure, so there were few open seats.

One time he asked if it was OK to sit next to me. I said “sure,” although I would have preferred to keep that seat open. I just shut up and kept to myself. But it turned out that we were both big Phillies fans, and he was far chattier than me. So he asked me where I was going (“oh, love the Phils. Juan Samuel is amazing. Think they’ll win the division again?”), what I did for work, what about my family. Even though I still thought he was an obnoxious jerk, I couldn’t ignore him.

I still felt uneasy around him, so on a later trip, I reminded him of the episode on the Senate floor with Javits. Biden was shocked (“Whoa, I can’t believe I did that, how disrespectful I was”). He said that he still didn’t think busing was the right solution for segregated schools or the right thing educationally for kids (he didn’t say which kids), but he apologized for his outrageous behavior toward someone he admired and respected. I don’t think I’d describe him anything more than an occasional commuting acquaintance, but he had clearly grown up.

I still wasn’t sure about the “vacuous” part. Maybe he’s a nice guy but still a lightweight. I think it was in 1987, around the time he announced his first run for president, when he came to Penn Law School for an evening speech on foreign policy. His speech on America’s place in the world and the threats to and opportunities for America’s influence, 90 minutes without notes, is perhaps the clearest, most articulate, best speech I have ever heard on the topic. So I crossed vacuousness off the Biden demerits list.

But that was almost 40 years ago and arrogance seems to be back. And there’s another, more ironic parallel with Javits, a long-successful politician who ran again when he should have dropped out. In February 1980, Javits, the senior Republican on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, announced that he would run for a record fifth term as U.S. senator from New York.

Then 75 years old, he was still whip-smart, articulate and vigorous. I could barely keep up with him on the tennis court, much less keep pace with his speed-walking to the Senate floor or his office. But there was something newly odd about the cramped style with which he gripped his tennis racket or his pen. Probably just arthritis, I thought.

Javits tempered his announcement by stating that his doctors had diagnosed that he had a mild form of what they described as “motor neuron disease” that they said wouldn’t affect his mental acuity or his ability to serve another full term.

Believing fervently that New York Republicans and the general electorate would continue to support him owing to his impressive record of legislative success, constituent services, and the seniority he had built up, he ran a lackluster primary campaign, preferring to concentrate on his legislative responsibilities in Washington.

In early September, he lost the Republican primary by a 56%-44% margin to a relative unknown, a local Hempstead township official, Al D’Amato, who also had the Conservative and Right-to-Life party endorsements. Only 20% of New York’s registered Republicans voted in the primary.

Javits, still believing a plurality of voters wouldn’t turn him out of office, stayed on the November ballot as the Liberal Party candidate and began to campaign more assiduously against both D’Amato and the Democratic candidate, Congresswoman Liz Holtzman. By early October, Javits was polling around 25% and believed that, after getting the endorsement of Al Shanker and New York’s biggest teachers’ union, he was gaining enough momentum to win the three-way race.

D’Amato’s strategy was to keep the Republicans who hadn’t voted in the September primary but who had previously voted overwhelmingly for Javits in prior general elections from doing so again, so he ran TV and print ads that, Javits complained, “make me look like I was dead.” In the end, D’Amato beat Holtzman 45%-44%. Javits got 11% of the vote and is believed by most observers to have spoiled the race for Holtzman.

By 1982, Javits, who had ALS, was in a wheelchair; by 1984, he was unable to speak except through a machine. He died in 1986, several months before what would have been the completion of his fifth term.

Javits, generally considered to be the smartest man in the Senate, could be arrogant too. But he wasn’t so arrogant as to not request, receive and disclose his diagnosis. He believed fervently that he could still serve and that the voters would agree. The doctors did; the voters didn’t.

Biden’s refusal to withdraw isn’t simply a product of the stubbornness and self-certitude — yes, arrogance — that is part and parcel of a politician who has been electorally successful for more than 50 years, but is also a symptom of his current and likely future cognitive condition. He’s said he will stay in the race and that the voters will decide.

But America’s voters deserve to know, with confidence, whether he will be able to complete his term and serve out a second with the clarity and vigor that a president must display on a daily basis. So Biden must have and disclose, as George Stephanopoulos suggested in his ABC News interview, a full neurological evaluation, one that includes a brain scan, which is a far more predictive test than the Montreal Cognitive Assessment that Donald Trump brags that he consistently “aces.”

And he should challenge Trump, another stubborn, more arrogant and perhaps sicker old man, to do the same. That would be equally revealing and would “be wild,” as they say. At least it would provide more essential comparative information to voters — comparing the candidates’ plaque and lesions — than did their childish banter about the length of their….golf drives.

Javits, whose opponent hammered home to voters that he might not be able to serve out another term, saw his staying in the race merely helping elect a mediocrity who did little damage. For Biden, who clashed with Javits on the Senate floor nearly a half century ago, the stakes are far far greater if he makes the same mistake.

Morse, a former Senate aide, later served as chief communications officer at several national philanthropies.