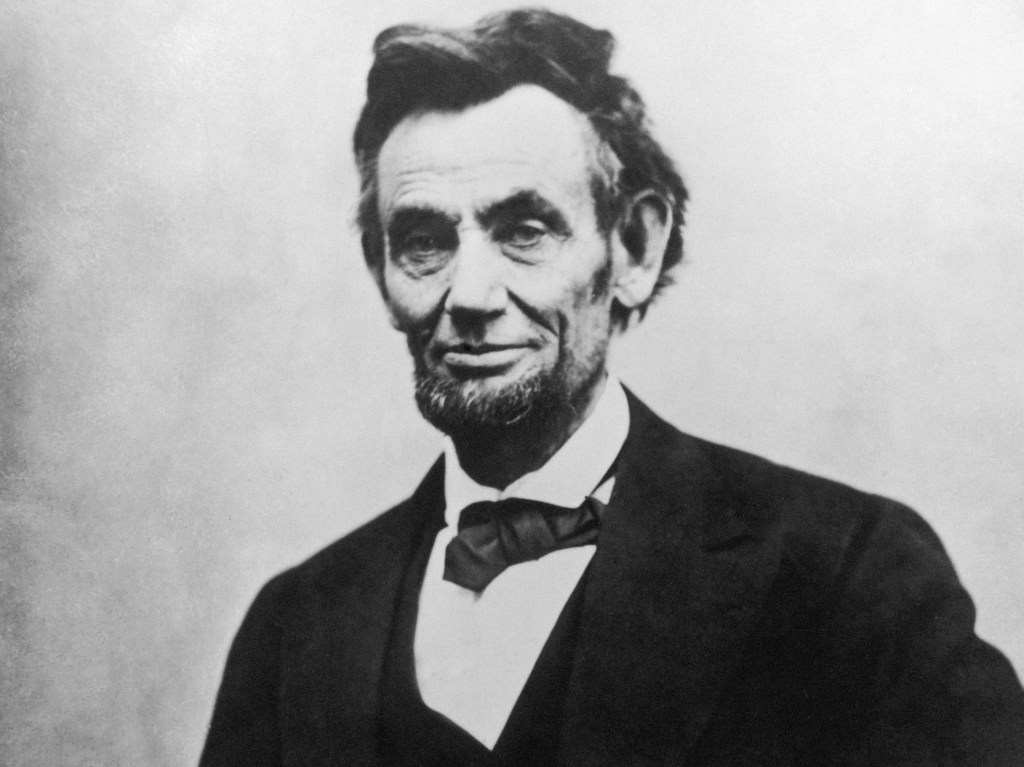

This July Fourth, migrants desperately making their way toward our southern border to seek asylum in the U.S. will face entry bans under the executive order issued a few weeks ago by President Biden. Biden’s policy shift calls to mind an earlier July Fourth presidential gesture — but a more generous one: an all-but forgotten bill Abe Lincoln signed into law in 1864. The legislation he approved that day turned out to be the last pro-immigration measure signed by any American president for more than a century.

Lincoln — known principally as the savior of the Union and father of emancipation — has not earned enough historical attention for pushing this all-but revolutionary reform, designed to swell immigration into the bitterly divided country. He not only signed the “act to encourage immigration” on Independence Day, but did so in the midst of his campaign for reelection to the White House, one in which he faced a significant third-party challenge. As someone once said, history doesn’t always repeat itself — but it echoes.

True, the situation in 1864 was not quite what it is in 2024. Immigration, which had swelled to as many as a million people a year beginning in the late 1840s, had dwindled to a trickle with the onset of our dangerous and deadly Civil War. Meanwhile, three years of bloody fighting had cost hundreds of thousands of American lives (among them, countless foreign-born soldiers, who eventually made up 23% of the federal armed forces). By 1863, death, injury, and illness had depleted both the army and the civilian workforce.

Defying years of hostility by nativists, Lincoln decided, just weeks after delivering the Gettysburg Address, to stimulate immigration afresh. In his annual message to Congress (the equivalent of today’s State of the Union messages), he called for creation of the first federal immigration bureau, regulations to improve conditions aboard ships that transported immigrants, and expansion of New York’s Castle Garden landing station, where 70% of all European refugees entered the country.

But he also called for a truly radical reform: federal funding to pay the cost of immigrants’ transatlantic passages. This proved a bridge too far for Democrats and Republicans alike. Lincoln settled for a compromise authorizing private financing that still provided impoverished emigres with money to cross the ocean. Once they arrived, Lincoln believed they would fill labor shortages on farms and in factories and mines, or, in return for a cash bonus, join the federal military. As a further incentive, the government offered free Western homesteads to immigrants — even before they attained citizenship.

The flood of new arrivals resumed. Within a year, Lincoln came to regard immigration as not only a practical solution to the national manpower drain, but as a policy designed by “Providence” to replenish a nation buffeted by internal strife and mass mourning. So he said at his next and final annual message.

On this Independence Day 160 years later, with jobs again going unfilled, Lincoln’s humane and sensible policy is worth remembering — and emulating. So is what Lincoln had declared at an Independence Day rally six years earlier.

Speaking in Chicago in July 1858, then-Senate candidate Lincoln paid the expected tribute to the “race of men living in the day” of the Revolution as well as their descendants. Then, to the surprise of many in the audience, he saluted the “Germans, Irish, French, and Scandinavian — men that have come from Europe themselves, or whose ancestors have come hither and settled here.”

“If they look back through this history to trace their connection with those days by blood,” he conceded, “they find they have none. But when they look through the Declaration of Independence they find it says ‘all men are created equal,’ and that they have a right to claim that moral promise as though they were blood of the blood, and flesh of the flesh of the men who wrote that Declaration, and so they are.”

Lincoln never believed immigrants were “poisoning the blood” of America — but, rather, enriching it. As president — and presidential candidate — he greeted them not with a clenched fist, but an open hand. Inclusion, he insisted, was “the electric cord…that links the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving men together.” No matter what side of the ocean, or the border, they were born.

Lincoln’s support for immigrant rights has been neglected by history — and deserves to be remembered now. Especially on a holiday he twice dedicated not only to the founding fathers but to immigrants and their children.

Holzer, director of Hunter College’s Roosevelt House, is the author of “Brought Forth on this Continent: Abraham Lincoln and American Immigration.”