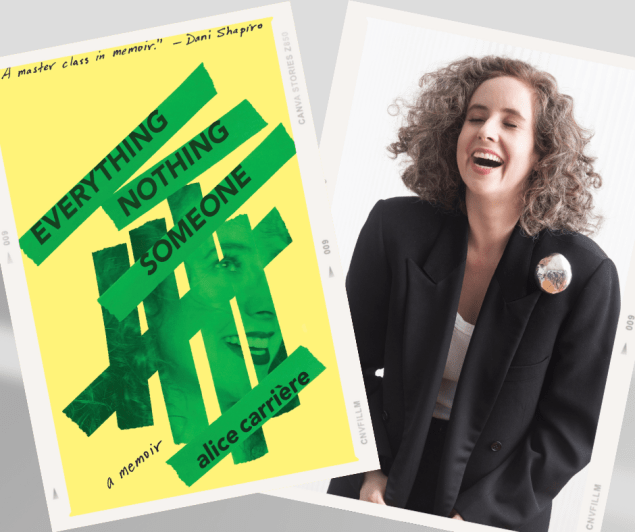

Alice Carrière’s memoir, “Everything/Nothing/Someone” is like a primal scream. The only way out of the pain is through it, and Carrière is up for the task. It’s no wonder acclaimed writer Dani Shapiro called her debut “a master class in memoir,” and Sarah Jessica Parker called it “extraordinary.”

From the outside, Carrière’s world dazzled. She’s the daughter of artist Jennifer Bartlett (widely known for her epic 153-foot painting, Rhapsody, in the permanent collection at MOMA) and the renowned German actor Mathieu Carrière. Bartlett was a staple of New York City’s celebrity circuit. In Carrière’s world, Anna Wintour dropped off clothes at Bartlett’s 17,000-square-foot townhouse in the West Village, Steven Martin joked at the table and Joan Didion sipped vodka on the rocks in Bartlett’s garden.

But the glamour was a facade—one that Carrière boldly obliterates in telling her story. Her talented mother was an island unto herself, her father was immature and made sexually inappropriate remarks to Carrière and her parents’ marriage dissolved in a bitter divorce. Behind the scenes, Carrière self-harmed, developed a dissociative disorder, abused drugs and alcohol and endured the worst of the American psychiatric complex. And yet, what begins as a memoir about suffering and disconnection ultimately ends with forgiveness and gratitude.

I interviewed Alice Carrière at the Soho Diner over hot chocolate and pecan pie, and I was rapt.

You’re so honest in your memoir that there were moments I felt uncomfortable, but that’s also what made it so good.

It didn’t occur to me while I was writing it that I could say anything but everything. I think the candor—not to pathologize it—might be a result of the dissociation because I feel as if I’m not real unless I reveal everything about myself to everyone. And then having the structure of that writing, it’s like a hug. It’s like that sustained contact that I’ve craved my whole life.

There was a time when you couldn’t recognize yourself in the mirror. Can you tell me about your experience with dissociation?

When I’m having a conversation with you I’m saying words I think make sense. There’s an impression of coherence and cohesion, but inside there’s this conversation that runs parallel to our engagement that can be really distracting… There’s also a level of the undifferentiated. There are no edges in a dissociated identity. But here we are. I am allegedly me and you are you.

It reminds me of Eckhart Tolle’s spiritual awakening. He was suicidal and he thought, “I can’t live with myself any longer” and then he asked, “Who is that I?” He became a witness to that voice.

It’s funny you mention that because I have a dear friend who is a Buddhist master, and he was telling me that what I describe sounds very much like an aspirational state for a lot of spiritual practitioners—this oneness with the world. And then I joke with him that on any given day I get to choose, is this a glitch or is it transcendence?

Not only was your mother a great artist, she was an icon surrounded by icons. How did she know so many influential people?

She was a brilliant artist, a voracious reader and really funny. She had amazing style and great parties. Who wouldn’t want to hang out with Jennifer Bartlett next to the pool [on Charlton Street] and crack open three bottles of wine? She had wide-ranging interests. She read everything about everything. She loved gardening. She loved theater. She loved to dance. She loved music. And everyone around her was smart and interesting.

And she was good friends with Joan Didion?

Very good friends. It’s so funny because I remember when I realized who Joan Didion really was. I had grown up with her and I was like, “Oh, that’s just that bird-like lady who drinks vodka-on-the-rocks in our garden.” Then I started reading her, and I got super weird around her. She then took me out to lunch after she’d read this awful novel I’d written at age nineteen. She later wrote me this incredible note that said, “There is no doubt you will lead a life of words. Thank you for sharing this amazing beginning, brilliant in so many ways.”

And you’d go on to write a brilliant memoir! Did your mother get to read it before she passed in the summer of 2022?

I gave her an early version, and she read it in a couple of hours. I sat outside in the living room, and I overheard her go, “Oh, incredible.” She said this out loud to no one, just to herself. And then I read her the first thirty pages of the final edit before she died. I had gotten the publishing deal, and I got to show her the book jacket too.

Then she read some of the more critical parts about her?

She did. I don’t see this as an indictment of her parenting. I am so grateful for everything she did. I have so much empathy for her. She liked to be surrounded by growing things, she always felt like she was killing things and that when she touched something, it would die. And I realized that her remoteness was an act of tremendous love.

She was trying to protect you from herself.

Absolutely. There is no petty resentment. She was one of the first female artists to make an incredible living off of her work. I have never met someone more passionate, more driven, more ambitious— the scale of her imagination! I saw Rhapsody while it was up at MoMA recently. I went up to commune with it, and I was so struck. It’s this piece that makes me unsure. It challenges the mechanisms by which I perceive the world. It also has such a sense of humor.

For research, I listened to an interview with her where she describes Rhapsody. She said that she wanted to make a piece that had no edges and that the space between the plates was the main actor. That made me realize that we had very similar preoccupations, and it reminded me of my own dissociated life where there are no edges, and where the gaps in the self are as significant as the more substantive parts of the self.

Your mother likely became a victim of the “Satanic Panic” that spread in the 80s and 90s. With her therapist, she unearthed memories of ritualized sexual abuse and murder that she turned into art. While you believe these memories were likely false, do you think she was sexually assaulted?

I wouldn’t be surprised. I don’t think that she was used in a sex cult or witnessed the murder of a young boy and was then made to bury the body on the beach. I do think that she was a woman in the world and that’s enough evidence for me that she was hurt. I don’t know who the culprit was. That’s the thing with this kind of trauma, it can be an accretion of small violations, or it can be one event. But there was damage. When she got to Yale, she would construct huge canvases that interfered with everyone around her because she was so nervous about being a woman there. I think that these false memories (which were outrageous and of mythic proportions —I mean, who can overcome satanic rituals?) made her inability to overcome her wounds seem more reasonable. In a way, it was disassociating from her reality, and I think she could feel less guilty about not being the partner or the mother she wanted to be.

You started to self harm at the age of seven. How’s your relationship with your body now?

It’s really interesting because I have a younger sister who’s a model and afraid of aging, and I have now entered this phase of my life of curiosity that has supplanted a lot of my fear. For example, let’s say my hair is going gray. I’m like “What is my body going to do next? How is it moving through time?” I also have existed as a size double zero and a size 16 because of the meds. It’s like an experiment. So I am profoundly interested in watching my body interact with time. It’s sort of what cutting used to do. I would cut myself, and then I would watch it heal.

Do you feel compassion toward your scars now?

I do. They feel like a chronicle or an archive that I’m wearing. It’s like the strata in a tree trunk. One therapist I had made me have a consultation with a plastic surgeon to see if I could remove them, but I didn’t want to because it felt like a connection to little Alice. This was the only way she knew how to speak. And now I look at my scars and I go, “Oh, that’s what you were trying to say.” But I wasn’t using the right language.

I haven’t cut in fifteen years. I don’t have a lot of cravings for drugs or alcohol, but very rarely I do crave cutting. It used to happen when I was feeling angry because I’m not good at directing anger outwards.

Neither am I. Women have been socialized to turn their anger inward. Are you angry at the doctors who irresponsibly overmedicated you?

I don’t feel anger towards anyone except these doctors. Because you place your trust, your hope, and your desire to be healed in them, and in response, they actually hurt you. I want to be super clear, though. I think responsibly medicating saves lives and good therapy is always a good thing.

There is a powerful love story that unfolds with your husband Gregory. When you were struggling, it seemed he saw something in you that you couldn’t see in yourself.

He was a conduit between me and the higher. He didn’t impose anything on me. He wasn’t even like, “You should be sober,” even though that was the clear conclusion. But it was that sustained contact where he was just there modeling a life of authenticity, integrity, compassion and service.

How did you get sober?

It was a total accident. I was weaning off of Klonopin, the last med to go, which has a notoriously difficult withdrawal. Everything went haywire. My hands twitched, I had no control over my thoughts, I had gastrointestinal problems and I felt an invisible hand was choking me. I didn’t want to put anything in my body that would alter my consciousness so getting drunk sounded very scary, even though it’s what I did a lot.

I got sober because I wanted to have control over my body and not drinking was a way to get that control. Only afterward did I realize I had a drinking problem. Then everything got better. Within a year, I had repaired most of my relationships, finished my memoir, and signed with an agent.

Your memoir shatters the idea that money can buy happiness. Do you believe your privilege delayed or helped your recovery?

If I had had to worry about pressing needs, I would have either risen to that occasion and gotten my shit together sooner, or I would be dead or homeless. It’s impossible to tell. It could have gone either way. But I mean, the privilege allowed me to stay alive and write this book.

Part of your healing was confronting your father, only to discover that there may have been misinterpretations. How are you able to hold the tension between how he wronged you and your love for him?

This book is about how many things can be true at the same time. My father behaved in ways that may not be excusable and that doesn’t disappear just because I’ve reconciled with him. Throwing light on the misunderstandings validated my lived experience, and knowing what wasn’t true, strengthened my relationship to what was. Listening to and legitimizing his experience fortified my relationship with my experience which made me better at believing myself and in myself.

Also, exercising empathy for him doesn’t diminish the empathy I feel for myself. I learned through this process that I get to decide what I believe, what I feel, and what I want to do with those beliefs and feelings. That choice is what’s empowering and holding that tension contributes to the tensility of my love for him and my love for myself.

When your mother became ill, you took on the role of caretaker. It seems like it was a turning point for you.

That’s true. It was reality and not my mind turning against me. It was the very real threat of time, and no amount of magical thinking could change that. It was like a crash course in being human.

There is a touching moment in the book when you are holding your mother down so her nurse can disimpact her colon, and you realize you’ve finally found yourself in your mother’s arms.

It was messy, funny, intimate and outrageous—all the things we could be and could be to each other when everything we demanded and everything we felt we’d lost wasn’t getting in the way.

The ending is stunning. Without ruining it, I’ll just say that you lovingly accept your mother’s proclivity to be alone, and she hands you a jewel of a metaphor.

It was like a cosmic gift. It was an incredibly painful and scary moment for both of us. After she died and I began to write about it, the ending revealed itself to be what felt like a transcendent collaboration, as if we were participating in and exchanging something sacred and vital. It was a gift not only of the perfect ending, but she gave me a way to understand our relationship in the exact manner in which we both interpret the world—in metaphors and symbols. I like to think that in the midst of grief, death and separation, it was an act of love, creation and connection.